Attribution - A Personal Story

First in a series about attribution

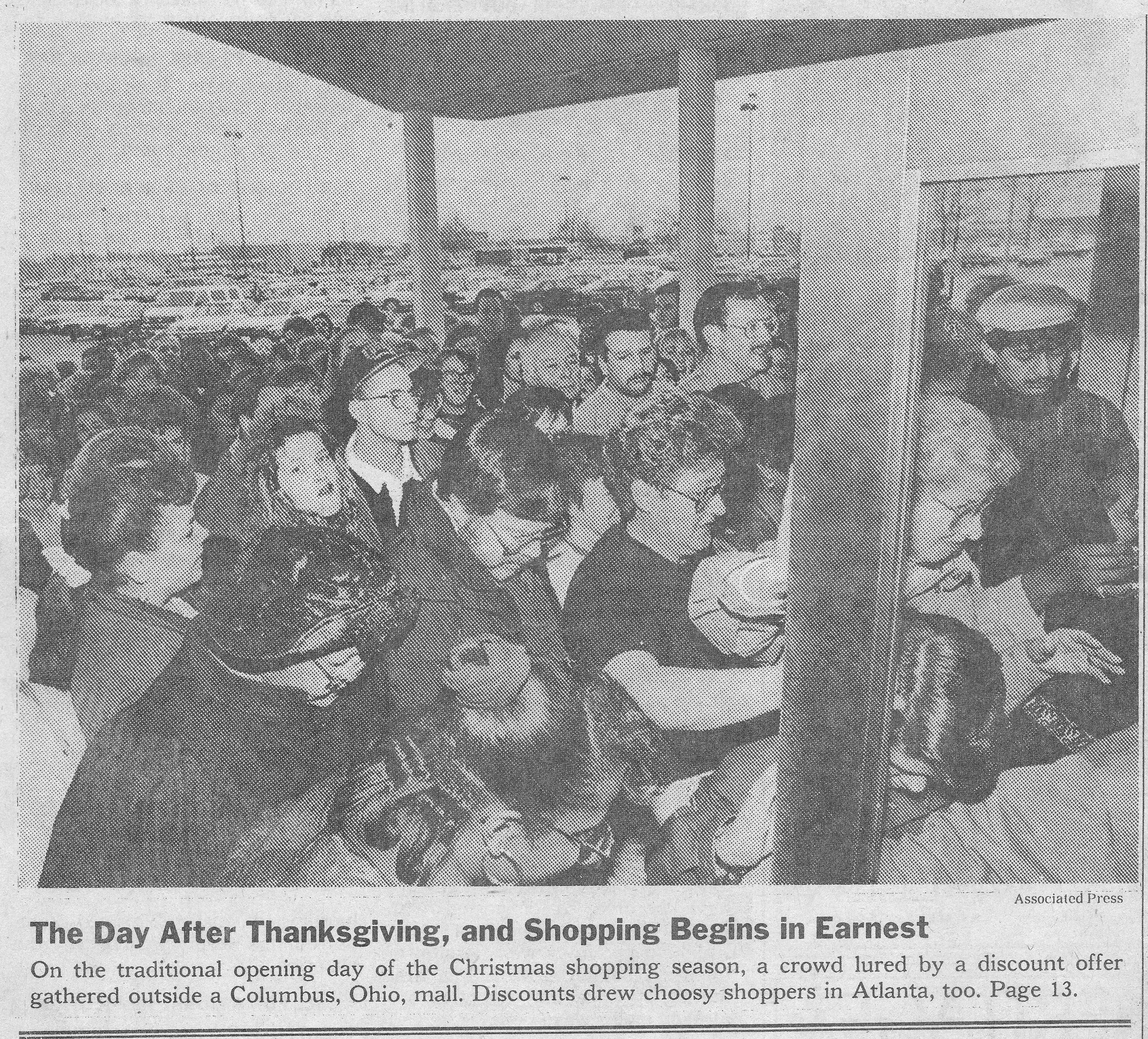

Photo by ??? of The Associated Press

Before the digital era, getting a photographer’s name set in type below a newspaper photo was more than complicated; it was nearly impossible. For those of us behind the lens, that meant our work often went uncredited.

Fortunately, by the mid-1990s, nearly all newspapers had transitioned from hot to cold typesetting, making it easier to transfer information from the computer to the press. However, inserting a wire service photographer’s name into the printed credit line still required extra effort from editors. They needed an extra step to format the caption, and from the back shop team, who had to cut a small name from a printed typeset paper, run it through a waxing machine, and carefully align it just below the photo.

That rarely happened with the credit line, since it was for me, working with the Associated Press, as shown in the photo above from 1993. I knew it was me. The bureau chief knew it was me, and the staff knew it was me. No one else knew.

To understand why credit lines were so complicated, consider how newspapers once relied on hot typesetting, where molten lead was cast into lines of type using Linotype machines, a system that dominated until the mid-20th century. By the 1970s and 1980s, most shifted to cold typesetting, first through phototypesetting and later digital layout, which replaced heavy metal slugs with film, paper, and eventually computer screens.

I disliked not having my name attached to my photos. I was anonymous, part of The Associated Press network, respected but anonymous. My identity, skills, and purpose were hidden behind the anonymity. Also, the reader had to trust the newspaper to know that, although my name wasn’t printed next to the photo, the reporting was accurate and truthful.

The great thing about being a photographer is that they must be where the story is happening. Television calls this an actuality, where the reporter speaks from the scene. Sometimes, news reporters can write a story without going to the location where the photographer is taking the photo to help explain the story.

For example, it’s common for a reporter to receive a credit line like "Story by Bob Smith" from the town where they’re reporting, without ever leaving the office. The story might be about something that can only be illustrated with a photograph from Westerville. This creates conflicting datelines between the story and the photographer.

Once, there was a discussion in the bureau about conflicting datelines. The story was datelined from Columbus, where the reporter wrote it. My photo dateline was Westerville, where I took the photo. An editor suggested I change my dateline to match the story’s, despite the fact I had been on scene and the reporter hadn’t left the bureau. I pushed back: “Why not change the story to Westerville?” That ended the conversation and proved the importance of photographic presence.

A dateline, the brief text at the beginning of a story, indicates to readers where—and sometimes when—the reporting occurred. It lends context and credibility, showing that the reporter was present or relied on reliable sources in that location. Typical datelines appear as a city name, such as “WESTERVILLE - ”

I believe that the photographer is sometimes the only person in the story who was present at the scene. A proper credit line with the name and company is the best way to fully attribute a photo to its source. That credit line, along with an accurate and complete caption, removes any confusion about the source.

Not including a photographer’s name in the credit line removes proper and precise attribution for the photo.

Digital Changes Everything

Everything changed in the late 1990s. With AP Photos going digital, what had once been a laborious process—wax, scissors, alignment—became seamless. Finally, names traveled with the images.

Now it is possible to electronically send the photo file with caption and full credit to a system capable of creating the page without the cumbersome cutting and pasting that slowed and frustrated the earlier process.

It didn’t happen overnight. It took months of discussions with newspaper photo editors and their supervisors to effect a change. It began with the largest papers and the smallest papers in Ohio.

Once one of them was convinced that complete attribution boosted its reputation as a trustworthy and precise news source, others would follow. Playing a smaller paper against a larger one, or vice versa, that was hesitant to change its inefficient process, was the key. Eventually, across Ohio, every AP member newspaper used the photographer’s name in the credit line.

That gave the photographer a clearer identity, one that matched the reporters whose names accompanied their stories. Newspapers now had a more complete line of attribution for stories and photos they published. Readers no longer could question the authenticity of a photo and could recognize the names of photographers just as they did with reporters.

Photo attribution became a stabilizing factor in a newspaper’s reputation, reinforcing readers' trust.

In the next F8 News -

Seeing Isn't Believing: How Attribution Can Fight the Visual Lie

Today, when appearances often overshadow authenticity, we’ve conditioned ourselves to pursue image over substance. Faux stitching on boots and car seats creates the illusion of craftsmanship without actually providing it, just as filtered Instagram lives are crafted more for engagement than for honesty. Reality, increasingly, is seen as an aesthetic choice rather than a grounded fact.