Some time ago, one of my Facebook friends pointed me towards a New York Times story with a remarkable photo of a lone person walking through dust and debris in a canyon of buildings destroyed by the war in Syria.

I always enjoy our conversations because we each have strong opinions, don’t always agree, respect each other, and love photography.

Today, we agreed that it’s complicated for a photographer to express pride or contentment when shooting photos like the one he pointed me to. It’s not an enjoyable task, shooting disasters and deaths.

I spent almost my entire photojournalism career shooting moments that weren’t necessarily enjoyable. There are plane crashes and auto wrecks. Funerals for police, firefighters, children, military, the famous, and the infamous.

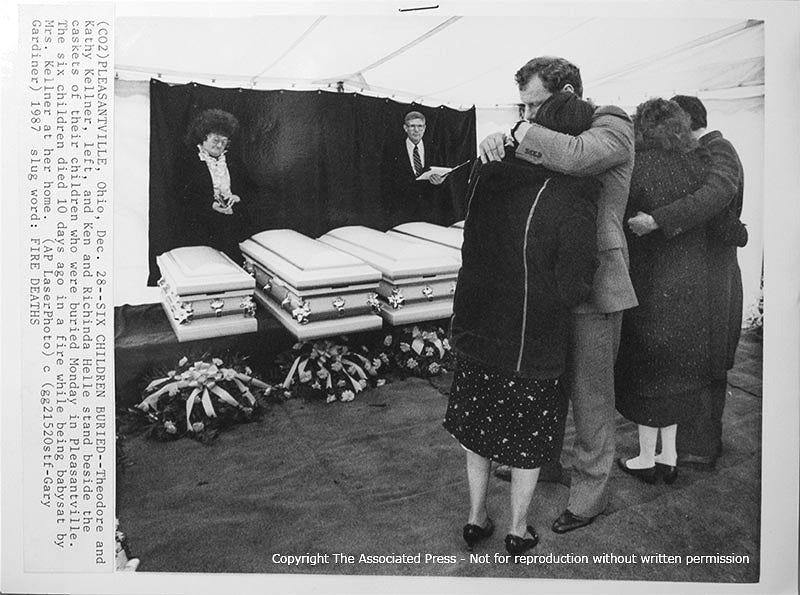

The photo above is one of those moments where journalism overcame emotion and fear in an attempt to communicate to newspaper readers the gravity of burying six children at the same time. As the caskets rested under the tent, an almost eerie silence enveloped the air, broken only by the soft rustle of leaves in the wind and the muffled sobs of grieving parents. The scent of fresh earth was mingled with the cold, crisp winter air, encapsulating the somber reality of loss. In that silent space, the weight of the tragedy felt palpable, capturing an emotion that words struggled to express.

There were only three frames of film from this viewpoint. I walked up to the crowd of mourners carrying one camera with a wide-angle lens. I stood quietly at the edge of the crowd gathered tightly against the tent covering the families and the caskets. I stayed quiet, my camera concealed under my winter coat, until I could see through the space between the heads of several mourners that emotion had reached its zenith. I hesitated, my heartbeat loud in my ears, feeling the weight of the moment and the story I was about to capture. The pause felt long, a battle waged within me between duty and respect.

As the parents hugged and the pastors said the final prayers, I reached over the crowd and fired three frames. No motor drive. These were film days, and cameras still had a thumb drive for moments just like this. In that moment, the guiding principle of truth-telling and bearing witness to history compelled me to capture the scene. It was not just about taking a photograph but about creating a public record, a testament to the children’s fleeting presence and the family’s profound grief. This task, though somber, was necessary to ensure their story was seen and remembered.

As soon as I shot the three frames, I returned to my car and left.

I knew I had photos to show the anguish of a funeral for six children. Also, I didn’t want to explain my actions to anyone. Driving away, I felt equal parts relief and unease. The photos were important, but the act of capturing them weighed heavily on my mind. My actions were cold and calculated. I anticipated one of the reactions would be anger at me. Still, the story needed to be told. I am a photographer. I did what was required.

No one chased after me. No one complained. There were no nasty letters from readers. I did receive congratulations for succeeding with a good photo in such a challenging situation.

I thought of this photo when I had my Facebook conversation, especially after what had happened the night before.

One of my granddaughters visited, wanting me to give her a bunch of black-and-white prints from my archive so she could decorate her room. Among her choices, in addition to the dogs, cats, and skunk photos, were photos of Jerry Rubin, Jane Fonda, Stokely Carmichael, a couple of presidents before Clinton, and assorted spot news photos.

Sandwiched in the collection now covering her walls are old news photos showing disasters, insurrection, injury, and recovery. As I looked at the photos now adorning her walls, I couldn’t help but reflect on the shift in their purpose.

All are now decorations for a teenager’s room. Once urgent records of pivotal moments, these images now serve as mere decoration. This reinterpretation made me question my sense of purpose, as it highlighted how an audience’s perception of photography can evolve over time.

They are wallpaper in black and white, blurred to the grays of history.

My Final Photo News is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my photography and commentary, become a free or paid subscriber. Subscribe to The Westerville News and PhotoCamp Daily. My Final Photo News also recommends Civic Capacity and Into the Morning by Krista Steele.