Truth in a System Built for Noise

Second in a series about attribution - by Gary Gardiner

From Saigon to Social Media

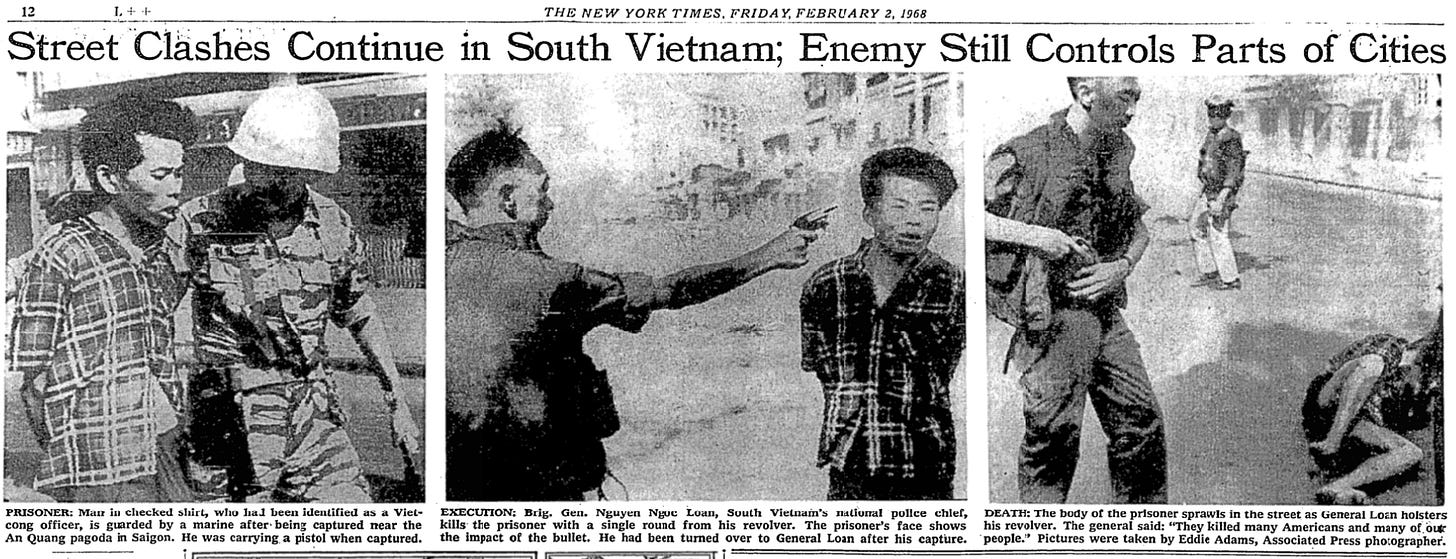

On February 1, 1968, Associated Press photographer Eddie Adams raised his Leica on a Saigon street and captured the moment when General Nguyễn Ngọc Loan executed a Viet Cong prisoner. The photograph shocked the world, shaped public opinion about the Vietnam War, and earned a Pulitzer Prize.

Its power rested on more than its content. Adams’ name was attached as part of the Associated Press photo caption. The location and date were known. The image was sent to newspapera cross the world with verification built in. Attribution — name, place, and time — made the photograph not just powerful but credible.

Note: There is a caveat. Even the New York Times did not use Adams’ name on the front page. It was relegated to page 12 where the story and photos continued.

Today, many images of violence or upheaval reach the public first through social media. They are stripped of attribution, often contextless, sometimes manipulated. Their trajectory depends on emotional punch and algorithmic preference, not editorial judgment. That shift makes teaching about truth in photojournalism more urgent than ever.

Attribution as the First Line of Truth

Attribution is the simplest, strongest safeguard. Every published photo should carry:

Photographer’s name — linking the image to accountability.

Location — anchoring the scene in geography.

Date and time — fixing the image in sequence, preventing false recirculation.

When these are absent, images are vulnerable to distortion, repurposing, and exploitation. Educating audiences to look for attribution is one of the most direct ways to resist misinformation.

Local Example: Westerville’s “No Kings” Rally

On June 15, 2025, Uptown Westerville held the “No Kings” rally on Flag Day, drawing thousands of protesters opposing Donald Trump’s return to the presidency.

The photos documenting the event did more than capture crowds and signs. They carried attribution in a simple form: visible watermarks on the images themselves.

The watermark, with photographer and location, is a visible act of accountability. It tells the audience: this photo is from here, from now, from me.

In an ecosystem where images are constantly stripped of metadata and recirculated without context, watermarking becomes both signature and shield. It reassures readers that they are seeing an authentic photo of Westerville’s rally and deters bad actors from misusing it elsewhere.

National Example: Tess Crowley and the Charlie Kirk Shooting

The value of attribution and professional restraint becomes even clearer when contrasted with a national breaking story. In September 2025, Deseret News photographer Tess Crowley was covering a Charlie Kirk speaking event when a shot rang out. Chaos followed — people ducked, screamed, rushed for exits. Crowley was knocked down but quickly regained her footing and began documenting what was happening around her.

Her photographs showed reactions: fear etched on faces, strangers comforting one another, law enforcement moving in. She filed her work with names, places, and times, producing a verifiable record.

Meanwhile, on social media, a different story was spreading. Graphic cellphone videos circulated instantly, fueling rumors of multiple shooters, conspiracy theories, and fabricated posts designed to stir outrage or generate clicks. Those unverified fragments traveled faster than Crowley’s careful reporting.

This is the divide: the professional photojournalist offered context, accountability, and restraint. Social media offered sensation, speculation, and distortion.

Crowley’s photos will endure in archives as evidence. The viral videos and fabricated posts will fade, but not before misleading millions. Her approach underscores why professional standards — attribution, verification, ethical framing — remain the backbone of trustworthy photojournalism.

Teaching Truth in a Complex System

Social media operates as a complex adaptive system. Its feedback loops reward confirmation bias: people share what matches their worldview, which algorithms amplify, allowing distortion to outpace correction. Distrust of institutions compounds the problem.

In such an environment, education cannot stop at slogans. It has to show the practices: attribution in captions and watermarks, restraint in visual choices, transparent verification. Professional examples — Eddie Adams in Saigon, Westerville’s rally coverage, Tess Crowley in Utah — demonstrate that truth is not abstract. It’s a practiced discipline.

Why Truth Still Matters

AI-generated visuals multiply daily, flooding timelines with fabrications that look convincing but lack accountability. In this flood, authentic photographs — attributed, verified, ethically framed — gain new value. They are scarce, not because cameras are rare, but because responsibility is.

Teaching truth in photojournalism may not “fix” social media. But every time a photo carries attribution, every time a watermark marks it as authentic, every time a professional like Tess Crowley resists the pull of sensationalism, the public record is protected.

Complex systems may never stabilize completely, but small, persistent acts of accountability, including a name, a place, a time, hold history together against the noise.

For those who want to go further, I’ll be building a Photo Literacy Toolkit in upcoming issues. It will include:

How to spot attribution in professional photos.

Simple tools for verifying images online.

Learn how photos are stripped of context and reused in misleading ways.

Case studies from both local reporting in Westerville and national stories like Crowley’s.

In a noisy system, truth survives only if we practice it, teach it, and demand it.

In the next F8 News -

Attribution as Antidote to Visual Misinformation in a Culture of Aesthetic Illusion

In a visually dominated culture where appearances frequently eclipse authenticity, the role of attribution is gaining new importance as a safeguard against deception.

“Seeing Isn't Believing: How Attribution Can Fight the Visual Lie” highlights how society has grown accustomed to valuing image over substance, with examples ranging from faux stitching on consumer products to highly curated social media posts. These visual cues often imply qualities—such as craftsmanship, success, or emotional wellbeing—that may not be present in reality. “It just needs to pass the eye test.”

My Final Photo News is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my photography and commentary, become a free or paid subscriber. Subscribe to The Westerville News and PhotoCamp Daily. My Final Photo News also recommends Civic Capacity and Into the Morning by Krista Steele.